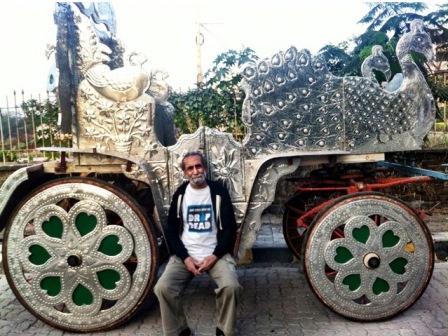

He says men’s engagement with women’s issues can bring about empowerment. Harish Sadani is truly an activist for all seasons.

by Vrushali Lad | vrushali@themetrognome.in

An ad in the Indian Express caught Harish Sadani’s eye in 1991. The Mahim resident was intrigued by the ad, an appeal that read, ‘Wanted: Men who believe that wives are not for battering. If you are a man wanting to stop or prevent violence against women, please write to Box No. _____’.

“I responded to that ad, and so did 205 others,” Harish remembers. We are at a bus stop outside Dadar station, but the unceasing traffic does not once break into his thoughts. “The ad had been put there by the Express’ journalist CY Gopinath. He analysed all the letters he received, and all of the letters were personal perceptions of the issue of violence against women and how it must stop. Of these 205 men, 99 were from Mumbai. He called all 99 Mumbai men for a meeting in early 1992.”

That meeting, and the fact that the same issue had been haunting Harish for a long time already, was to change the course of his life. “I was volunteering with a women’s rights organisation, but their manner of ‘punishing’ men who harassed their wives through public humiliation, was not something I agreed with. So this meeting came at the right time. About 25 men came for the meeting, and one of them was a 14-year-old school boy!” The meeting largely focused on the men’s opinions about how to end violence against women, and was the start of many more meetings.

“We would meet periodically to address the felt needs of men, what needed to be done to address the issue in a different, non-threatening way. We spoke to lawyers, doctors and psychiatrists, did research for a year. Then we came together and formed Men Against Violence and Abuse (MAVA) in 1993; there were about nine of us who started it.”

Harish has been MAVA’s secretary from its inception, and is the only person with a Masters in Social Work (MSW) degree from TISS, Mumbai. “What motivated me was that if I could take on the mantle of responsibility, I could be a part of a large movement for the future,” he explains. Today, Harish has won recognition for his efforts in promoting gender equality, and was the recipient of the Ashoka Changemakers award two years ago.

A ‘sissy’ writes to Smita Patil

Harish was brought up in a Mumbai chawl, an ecosystem where everybody’s homes look into your own and where nothing is really ever private. “I was witness to a lot of domestic violence, both in my joint family and in neighbours’ houses,” he remembers. “I would think about it for long, wondering why men hit women at all. My early life was shaped by my paternal aunts, who taught me that there was no shame in doing ‘women’s work’.” So he braved taunts and jibes of being a ‘sissy’ from friends and neighbours when he stood in line at the ration shop to get kerosene, or when he helped the women with their chores at home.

“I was already questioning gender roles in society. In my teens, I was very influenced by Smita Patil’s films, because she played very strong characters. I got her address from the magazine Madhuri, and began writing to her.” The legendary actress was initially taken aback by the young man’s several questions on gender issues, and what she felt about them. “She once wrote to me saying, ‘Your letters are the only fan letters I have to think deeply about before replying to,’” he grins. “She had a huge influence on my life. In fact, I decided to study MSW after watching her in Umbartha, because she also does the same course in the film!”

Involve, don’t isolate men

Throughout his journey as an activist, Harish has been insistent on one ideology – that men need to be a part of the solution. “It is one thing to identify them as perpetrators of violence, but it is wrong to exclude them. Men are not born violent, they are conditioned by patriarchal society to be masculine’ and they are trapped in this image. We must question this image and break out of it.”

MAVA started their work with street plays, counselling and awareness programmes on domestic violence. “But we did our first big job in 1995, when a student Dipti Khanna became the victim of an acid attack. Private donors gave us Rs 75,000 in two months for her plastic surgeries, but the most touching contribution came from prisoners of Nashik Central Jail, who contributed Rs 12,000 of their hard-earned money for Dipti,” Harish smiles, adding that this gesture built a lot of credibility for MAVA.

“We have always taken a stand on issues, be it the Bhanwari Devi case or the series of attacks on women arising from jilted love,” he says. “In 1996, we started the magazine Purush Spandana, a men’s-only magazine that we bring out in Diwali every year. Besides this, we have started various youth initiatives in colleges, Yuva Maitri, plus a helpline for the youth.” Harish has upscaled his efforts in Pune, Satara, Kolhapur, Bhandara, Buldhana and Nagpur as well. “We are encouraged by young boys wanting to engage with gender equality,” he says. “Their involvement and work is a throwback to the time we started MAVA, and when we took ownership of the same issues 20 years ago.”