The Akanksha Foundation’s Chitra Pandit explains why free education in BMC and PMC schools doesn’t always attract quality teaching staff.

by Vrushali Lad | vrushali@themetrognome.in

Part II of the ‘Little People’ series

A willing NGO and more than willing students need good teachers. Even a relatively well-known NGO like the Akanksha Foundation finds it difficult to get good teaching staff.

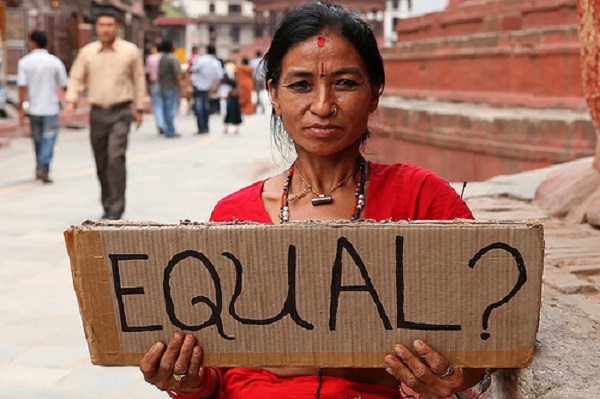

“Our biggest challenge lies in getting good teachers for our schools,” says Chitra Pandit, Director Marketing at the Akanksha Foundation, a non-profit organisation that works in the field of education for children from low-income families. “We have 13 municipal schools between Mumbai and Pune. The model is this: the BMC (or PMC) provides the school building, the students’ uniforms, textbooks and school bags. We provide the rest.” The schools follow the SSC curriculum and have 30 students per class. The teaching is free.

She rues the fact that despite scores of willing parents – there have been instances where more than the stipulated number of 30 students to a class had to be crossed due to overwhelming demand – who want to send their children to their schools, quality teaching personnel are hard to find. “It is a fact that we don’t get the cream of the teaching talent available. The BMC insists that all teachers must have a B.Ed degree, at the very least. But then, those with B.Ed degrees want to teach in reputed private schools. So we have gone into non-B.Ed colleges to scout for potential teachers, assuring the BMC that we would get them to complete their B.Ed at a later stage.

We’ve advertised in mainline dailies, we’ve made our website stronger, we also send out mailers to our contacts and friends, asking them to recommend teachers or spread the word. We’ve actually started recruiting people who are graduates.”

Since no fees are charged but operational costs per school are quite high, the Foundation depends heavily on donors and sponsors. “However, we have not been able to get any new donors on board recently,” Chitra admits.

With the teachers that they do have, however, there are certain parameters that must be met. More parents from the poorer sections of society are insisting on sending their children to English-medium schools today. “Due to the lack of adequate teaching support at home, we have to make doubly sure that they study well in the classroom. They cannot afford private tuitions after school hours, so the teaching in school has to be perfect,” Chitra explains.

Chitra explains that apart from the challenge of dealing with children from underprivileged backgrounds – most of them are first generation learners with no exposure to the English language –the teachers also have to work harder at giving the proper amount of attention to each child, to address their concerns in a caring manner, and to be really patient with the students. The students’ parents belong to the service class – common occupations are domestic help, security guard, driver and vendor – and their incomes, like their own education levels, are generally low. “An inherent quality of patience is a must for the teacher, especially owing to the students’ backgrounds,” Chitra says, adding that the 200 teachers in their Mumbai and Pune centres and schools are tested extensively during their interview rounds.

“Most teachers are aware of the students’ backgrounds, but we also try to gauge their interest in teaching and handling a class right from the interview stage. We ask them to prepare a subject and do a quick demo in a class – this helps us understand their aptitude and preparedness,” she says. Selected candidates are trained in a two-week residential programme, where the Foundation works with them on various fronts. “The focus is on classroom management and academics, but the basic passion for teaching and the skill must be there,” Chitra says.

Diaries is a weekly series of stories on one issue. ‘Little People’ is a series of three stories on the education of underprivileged children in Mumbai. Look out for Part III tomorrow.