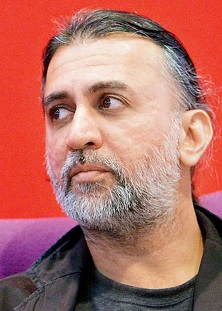

By saying ‘These things happen’ in the context of the Tarun Tejpal case, we are sanctioning sexual predators’ ‘small’ crimes.

by Jatin Sharma

Mumbai has always been contradictory. It is known as the city of dreams, but it is also the city that never sleeps. From the 1960s on, people have been howling about the lack of space in Mumbai and how noone can find a house here, but the builders keep making houses and buildings by the hundreds. A city that is considered to be the most aware in India is still a laggard when it comes to voting. The financial capital of India also houses the biggest slums. Some members of the ‘elite’ janta will shudder in horror at the prospect of partying at not-so-happening joints, but will come out to eat anda bhurji on the bonnets of their BMWs. Mumbai is and always will be about contradictions.

I was reminded of this fact today when I heard people talking about Tarun Tejpal’s sexual assault case. Straining to hear a discussion about the case on a Mumbai street, I was sure I was going to see the city’s contradictory side again. And sure enough, there it was: “It’s not that bad, yaar. These things happen all the time in offices, everywhere,” was a statement often repeated amongst the group.

And so it happens.

This is the same city that simmered with fury last year in December when a girl in Delhi was raped. This was the same city that went on protest marches and endlessly discussed rape and how women were unsafe when a journalist was raped in the Shakti Mills compound by, er, ‘poor people’. Today, during a discussion with my colleagues, someone mentioned that in the Tarun Tejpal case, the victim must have wanted to get into the ‘good books’ of Tarun Tejpal and “that’s why must have done it. This happens all the time and in all sectors,” was the explanation.

This is the same city that simmered with fury last year in December when a girl in Delhi was raped. This was the same city that went on protest marches and endlessly discussed rape and how women were unsafe when a journalist was raped in the Shakti Mills compound by, er, ‘poor people’. Today, during a discussion with my colleagues, someone mentioned that in the Tarun Tejpal case, the victim must have wanted to get into the ‘good books’ of Tarun Tejpal and “that’s why must have done it. This happens all the time and in all sectors,” was the explanation.

Even if a girl is alone with you in your room, that doesn’t mean she wants to sleep with you. Sure, women are difficult to figure out, but understand one thing: when a woman says ‘no’, don’t take it to mean ‘yes’ or ‘maybe’.

A recurring point being made by several people is: ‘This crime is not so bad’. My question was and remains: Why? Why is it not ‘so bad’? What makes a crime ‘bad’? Must the victim cry incessantly and refuse to come out of her house to convince us all that the matter is serious? Why is molestation a ‘smaller crime’ than rape or murder? Why don’t we see this as a problem? On the one hand, we want a society that is free from malice and then we start to define the degrees of malice ourselves. A crime cannot be bigger or smaller in comparison to others. A ‘small’ case of molestation that goes unnoticed and unaddressed empowers the criminal to attempt a a more serious crime.

What’s more, I can’t digest this idea of delegating a professional or personal sphere to a crime. The journalist who is fighting for justice right now was certainly an employee and may have partied with the boss, but that doesn’t make her ‘that’ type of girl. Even if a girl is alone with you in your room, that doesn’t mean she wants to sleep with you. She might be drunk and it may be 3 am, but that doesn’t mean she is allowing you to make overtures. If you read that last line and thought that I was wrong, then maybe you need to adjust your thinking a bit. Sure, women are difficult to figure out, but understand one thing: when a woman says ‘no’, don’t take it to mean ‘yes’ or ‘maybe’.

With respect to this case being discussed endlessly in newspapers and on news channels, all I can see are judges around me, dissecting the girl’s moral character. What gives us the right to demean an individual who has the courage to go against someone as powerful as Tarun Tejpal? What gives us the right to say, “Oh, but these things happen at the workplace,” so casually? Yes, these things must be happening around you, but not all the victims are as courageous. Most victims let the bosses who took advantage of them during weak moments go scot free. With examples like the Tejpal issue, maybe figures in authority will realise that employees are to be appraised on the basis of their professional skills alone, and they cannot threaten an individual and force themselves upon any girl just because the girl is on his payroll.

to demean an individual who has the courage to go against someone as powerful as Tarun Tejpal? What gives us the right to say, “Oh, but these things happen at the workplace,” so casually? Yes, these things must be happening around you, but not all the victims are as courageous. Most victims let the bosses who took advantage of them during weak moments go scot free. With examples like the Tejpal issue, maybe figures in authority will realise that employees are to be appraised on the basis of their professional skills alone, and they cannot threaten an individual and force themselves upon any girl just because the girl is on his payroll.

Jatin Sharma is a media professional who doesn’t want to grow up, because if he grows up, he will be like everybody else. ‘Overdose’ is his weekly take on Mumbai’s quirks and quibbles.

(Pictures courtesy onwardstate.com, thebodypacifist.wordpress.com, www.mid-day.com)