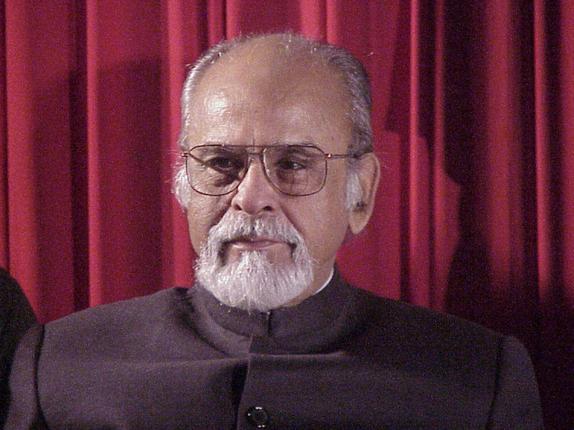

Humra Quraishi writes on the demise of IK Gujral, and what she first thinks of when she hears his name.

I heard the news of former Prime Minister IK Gujral’s demise, and the very first image that floated in my mind was of him and his poet wife Sheila strolling in the Lodi Gardens. They wouldn’t walk formally, like most married couples do, but like two close friends, hand in hand.

I heard the news of former Prime Minister IK Gujral’s demise, and the very first image that floated in my mind was of him and his poet wife Sheila strolling in the Lodi Gardens. They wouldn’t walk formally, like most married couples do, but like two close friends, hand in hand.

It was such a lovely sight to see the two together. This is not a tale of ancient times, but something that happened just about 12 years ago. I used to live in New Delhi then, and I’d go running towards those gardens to try and control my high blood sugar levels. And whenever I would see this couple, I would stop and stare at them, sometimes for minutes. My own marriage was nearing a stage of collapse, and later it did collapse totally, so whenever I’d see couples in love walking in that romantic way, I‘d stare at them enviously.

But let me not get carried away with my romantic reminisces, and focus on IK Gujral in a wider, bigger way, as his younger brother, artist Satish Gujral has done in his autobiography, A Brush With Life. There’s an entire chapter in this volume on Inder Gujral titled ‘Friend and Brother’, and carried several political details and many important socio-political backgrounders. But if you were to know the actual traits of his personality, you must read the entire book, for it certainly brings out Inder Gujral as somebody who was always a class apart from the rest.

To quote Satish, “With my father’s indifference towards the household, the authority to make decisions had passed on to my eldest brother, Inder. Though he was still in his teens, he was recognised as the heir apparent. He was not the first born child of our parents, but the first to survive; my father doted on him. Inder had inherited many of his traits.

This affinity of temperament drew them close to one another…the audacity of spirit which Inder demonstrated when he took to politics was undoubtedly inherited from our father. Inder was only ten years old when, like our parents, he courted arrest. Although he was kept in the police station only for a night, his actions reassured my father that his son was following in his footsteps…”

The passages where Satish writes of his near-fatal accident in Pahalgam’s Lidder river – which left him severely injured and impaired his speech and hearing – brings out the supportive role played by his brother Inder. In later years, Satish embarked on his artistic journey. “Inder found an art school in Lahore where I could learn drawing, painting, sculpting and much else…” And later when Satish shifted to Mayo, the bond between the brothers deepened.

“The one thing I could not stomach in Mayo’s hostel was tasteless and badly served food. My father, who knew how fussy I was about food, arranged for me to eat in Inder’s hostel, which was only half a kilometre away. Joining my brother every day for meals brought us closer to each other. Besides eating with him, I learnt a great deal from him about literature and poetry, and above all, how personality was moulded by commitments.

He also sensed that my resentment and frustration at being handicapped was building up to a climatic rage, which, unless channelled into creative pursuits, would be my undoing. It was Inder who infused in me a fervour for social revolution. He felt that this would ease my burden and instil in me the hope of a better world.”

Humra Quraishi is a senior journalist and author of Kashmir: The Untold Story, and co-author of Simply Khushwant.