The disorder can wreak havoc with a person’s life, and he or she can wither away before your eyes.

by Humra Quraishi

by Humra Quraishi

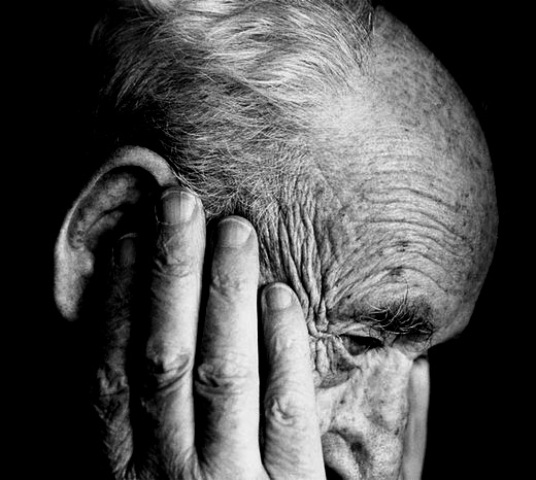

Those affected by the Alzheimer’s disorder change drastically, beyond recognition. Their memory becomes ‘polka dotted’, with only little islands of memory remaining. With pathological changes in the brain beginning to take place, the affected person’s lifestyle and personality, and everything else connected with them undergo a sharp transformation. The affected person may get into a shell or turn aggressive, or could sit looking lost and forlorn. And as the memory cells deteriorate and decline, the affected person finds it difficult to recognise his or her children.

My family didn’t have the slightest clue about the Alzheimer’s Disorder (AD) until it struck home. My father, Iqtidar Ali Khan, started displaying symptoms soon after his retirement. He began forgetting mundane things and started slipping into depression. At times, he would sit all by himself, looking lost and forlorn, or else sit sobbing. When we would sit beside him and hold his hand, or hug him, he would feel reassured. We didn’t realise that there was something more to the apparent bouts of depression and forgetfulness.

Then, one day, my father got lost in the park. More such incidents followed. Though he had been driving for decades, he suddenly couldn’t drive with the same confidence. Then he lost the sense of roads and familiar settings.

Within weeks, my handsome and well-dressed father had changed. Earlier, he had been very particular about going to the club  for tennis or going on long drives, but within a short period of time, all that changed. He seemed lost, shutting himself into a shell…his memory shrank with each passing day. In effect, this is what Alzheimer’s roughly all about: shrinkage of the memory cells and the consequent degeneration.

for tennis or going on long drives, but within a short period of time, all that changed. He seemed lost, shutting himself into a shell…his memory shrank with each passing day. In effect, this is what Alzheimer’s roughly all about: shrinkage of the memory cells and the consequent degeneration.

My father passed away in 1996, but a couple of years before that, he couldn’t recognise us. He just stopped recognising us. His eyes conveyed restlessness, as though he wanted to say much or as if he was trying his utmost to connect with us and reach out. Sometimes he would murmur sentences and recall some incident, long gone by; something from his childhood or young life, maybe. Occasionally he would burst into tears, sob like a baby, and even go looking for his dead mother or his siblings.

One incident, in particular, shattered us. We saw him looking for something he seemed to have lost. He moved about restlessly, peering under beds, behind sofas and doors. When we asked him what the matter was, he spoke with restless impatience, “Where are my children? I’m looking for them. They’re lost! Find my children…are they lost or what!”

We were standing right there, staring at him in utter disbelief, but he couldn’t recognise us. He had been a doting father, helping us not just with our homework but even during the emotional turmoils of our lives. Always a family man, he would wait at the dining table and not eat before all of us had assembled for dinner or any meal. An engineer by profession, he would take us on his tours when he would supervise the construction of the various dams around Jhansi town.

I cannot describe how difficult and traumatic it is to see these painful changes. It is important to mention here that the role of the immediate family is crucial. The only time my father would look a bit peaceful was when we sat close by, holding his hand, clasping him as if to reassure him. Human bonding takes care of much of the pain that an AD-affected goes through.

(Pictures courtesy thinkprogress.org, www.cnn.com. Images are used for representational purpose only)