It was the worst of times, but yet, it may have been the best of times for a fourteen-year-old boy.

by Abbas Bagasrawala

I don’t remember the hatred. I do, however, remember the fear in my parents’ eyes as we were laid under siege in my all-Muslim building in Mazagaon, waiting up on our terraces for marauders that may have come, but never really did, probably more because of sheer dumb luck than anything else. I remember watching the city burn. Even at the age of 14, I realized that there was something wrong with the world if your city burned.

I remember being a little pissed off that, when the violence got too much for the pussy footing police, an army platoon or whatever was brought in and it encamped in St. Mary’s ICSE, foregoing my school, St. Mary’s SSC, which was just across the road. I reasoned it must be because they had ‘all those rich kids’, and was more bitter about this insult than any Ramjanmabhoomi issue anywhere.

I remember being a little pissed off that, when the violence got too much for the pussy footing police, an army platoon or whatever was brought in and it encamped in St. Mary’s ICSE, foregoing my school, St. Mary’s SSC, which was just across the road. I reasoned it must be because they had ‘all those rich kids’, and was more bitter about this insult than any Ramjanmabhoomi issue anywhere.

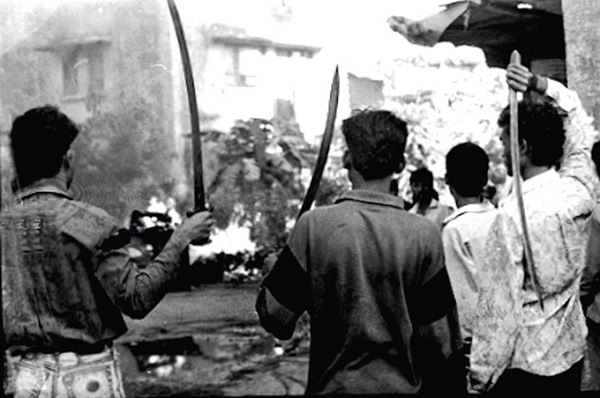

I remember seeing a mob armed with swords chasing down some guy on the bridge near our home and I remember the next scene as if it was in a B-grade movie, where the guy escaped by running and leaping with a grace and an élan that didn’t belong to those gauche times, into a BEST bus that was at that opportune moment passing by. The technique that saved his life could have only been learned after a lifetime spent training in the kung-fu art of running by the side of a bus before leaping into it. It was a technique that could only have been learnt in middle-class Bombay where those buses not just ferried you towards your hopes and dreams but also in most cases got you back home to your loved ones after situations that could only be described as murderous.

I remember my friend Murtuza being slapped across the face by an uncle in our building to save him from being picked up by that same army platoon because he burst some leftover Diwali crackers in mischief (the Army thought it was disturbing the peace) that arose from the boredom of being confined to our building playground that long holiday from school. Riots are not just destructive to life and limb, to person and property, but also to kids at home with nothing to do except wait for the rapture that is the break in the curfew. There was no cycling in the gullies, no cricket in the driveway, and no football in St Mary’s ISC. There was not even the remotest possibility of sailing, of catching a movie or walking to a dingy videogame parlor to blow pocket money on the Mario Brothers and Contra. Even our windows were kept closed because my parents took the shoot-at-sight orders way too seriously.

Time passed excruciatingly, mind-numbingly slowly. The riots had taken all that was good about life, and turned it to squalor.

Also while we were imprisoned in our building I remember hating the fact that I had to part with my cricket bat, my hockey stick, and some stumps to some of the older kids who were  apparently collecting sports goods for some grand sporty defense of the building, in case people decided to attack us. I was certain this was just some elaborate scheme to merely get their paws on our stuff. But most of all I remember the people who took the riot and made it something that I learned from, something that made me more secular, something that make me love Bombay more. They were the people who rescued Bombay from the riots, from the self-immolation that it seemed to be hell bent upon.

apparently collecting sports goods for some grand sporty defense of the building, in case people decided to attack us. I was certain this was just some elaborate scheme to merely get their paws on our stuff. But most of all I remember the people who took the riot and made it something that I learned from, something that made me more secular, something that make me love Bombay more. They were the people who rescued Bombay from the riots, from the self-immolation that it seemed to be hell bent upon.

I remember the neighborhood pavwalla (I called him the guy who really brought home the bread and butter in a private joke on my dad) who, when the curfew broke, delivered bread from his hole-in-the-wall-shop to the entire Lower Nesbit Road area where I lived. I remember how he used a quintessentially Bombay move on a rich prick who tried to jump the bread queue by stating in almost Delhi terms about how he was too important to wait in a line like everybody else. The move, which should be called The Pavwalla Checkmate, was to give that dude the bread first but he made that bastard wait, and wait, and he made him wait till the very end to accept his money. Rich prick could not walk away without bread because they were curfewed times and therefore bread was not easy to come by. Also rich prick could not simply walk away without paying for the bread because that would be cheap, which would defeat the very credo of being rich and being a prick. In a time of grave injustices, this was justice at its very best, doled out in the language of money, a language that was more Bambaiyya than any of the vernaculars used within.

If times of crisis differentiate men from the boys, then crisis merely forges legends into beings of even more awesomeness. This was the case with Rabi Ahuja, the erstwhile Commodore of the Sea Cadet Corps where I went for my bit of extra-curricular activity. I loved the Sea Cadets, mostly because they introduced me to sailing, which to do this day is an infatuation of mine, but also because they wielded words like ‘honour’ and ‘integrity’ to my upbringing of the time.

I loved the Sea Cadets so much that I managed to convince my parents to go for our usual Sunday Parade at TS Jawahar, Colaba despite the fact that people were killing people and the world had essentially gone mad. My arguments of the time were that rioters won’t be doing said rioting on Sundays cause that was arguably the day even the Gods rested and even rioters need a break. Also whilst at TS Jawahar we were safer than money in the bank. Besides, I argued, Captain (he was Captain Superintendent then) would make even the worst rioter literally shit his pants if they tried any funny business with the Corps. Of all my arguments, I think that the last one was the clincher for my parents, and I think that between the promises (had there been any) of the Indian Legal System and Captain Rabi Ahuja, they would have trusted him with us more without a moment’s hesitation. That was the nature of the man. That was the nature of his legend.

I loved the Sea Cadets so much that I managed to convince my parents to go for our usual Sunday Parade at TS Jawahar, Colaba despite the fact that people were killing people and the world had essentially gone mad. My arguments of the time were that rioters won’t be doing said rioting on Sundays cause that was arguably the day even the Gods rested and even rioters need a break. Also whilst at TS Jawahar we were safer than money in the bank. Besides, I argued, Captain (he was Captain Superintendent then) would make even the worst rioter literally shit his pants if they tried any funny business with the Corps. Of all my arguments, I think that the last one was the clincher for my parents, and I think that between the promises (had there been any) of the Indian Legal System and Captain Rabi Ahuja, they would have trusted him with us more without a moment’s hesitation. That was the nature of the man. That was the nature of his legend.

And boy, he did not disappoint, for when we did get to TS Jawahar at 7 am, he made us parade in the hot sun in a manner not too divorced from the times when everything was normal, as if everything had not gone to pieces like that mosque in Ayodhya, as if Bombay and India had not inexorably been changed for the worse. He stood, a fountainhead, for a better, less revolting time. He even staved off phone calls of petrified parents who by now were informing us that the rioters had not taken the day off and who were, in all earnestness, carrying on the glorious tradition of communal riots in this country. He assured those doubting parents that if needed he would personally people drop home if the situation required. To me, this was the epitome of taking ownership for your fellow Indian much more than any politician’s speech ever could. But even more than that, it represented an exciting prospect as being dropped home in Captain Ahuja’s Blue Premier 118 NE was akin to having the President of a country drop me home with full State honours. In my mind’s eye, I could see him driving us past problem areas and rioters, whoever they were, automatically stopped whatever they were doing to this city, and stopped to stare at a sight as rare and magnificent as this. After staring for a bit, I was sure that they would go straight home because no one, and I mean no one, had the cajones to kick up the dirt when the Captain made the rounds. After that my bro and I would have our glorious homecoming with all the neighbours looking on as a brilliant man, in a brilliant white uniform with a peak cap that the sun would be proud to be above, would stop at my gate, and we would salute him, because he stood for all that was the best of India, all that was  the best of this city and that would be just right, in a time of copious wrongs.

the best of this city and that would be just right, in a time of copious wrongs.

But alas, it was not meant to be. We never got that ride with the Captain, for we lived in a relatively safe neighbourhood, one which wasn’t so high up on the danger scales which meant that we caught the usual No. 3 bus home unescorted, returning to being merely children of the lesser God of the times.

Bombay, bas is a weekly column on getting around the madness of Mumbai and exploring the city with a fresh perspective. This column tells it like it is.

(Pictures courtesy www.outlookindia.com, www.indianexpress.com, asianetindia.com, www.seacadet.in, www.tehelka.com)

One reply on “The 1992 riots: a memoir”

What did you see as a child that affected you for the rest of your life?…

For me it was the 1992 riots in Bombay. Till then violence of any sort was linked to the movies and the fisticuffs I had with my kid brother. In the interest of not having a really long write up because I’ve already put it down, here’s a link to that…