Researcher Sadashiv Tetvilkar’s newest book on ‘veergals’ (aka hero stones) talks about memorial stones as unique sources of local history.

by Shubha Khandekar

‘Rural Maharashtra is strewn with hundreds of Veergals (Hero Stones) at the boundary of the village or else, in the courtyard of a Shiva temple located on the periphery of the village. A group of four beautiful Hero Stones (fifth one is in the custody of ASI) at Eksar in Borivali shows in vivid detail a ferocious naval battle, which has been correlated to the text Chaturvarga Chintamani composed by Hemadri Pandit. He describes a decisive naval battle fought between Yadava King Mahadeva and Shilahara ruler Someshvara in which the latter was routed and killed in 1265. The details of infantry, cavalry, elephant force and battle ships shown herein enables us to understand the military strategy deployed in this battle. Someshvara was cremated at Eksar and the five Hero Stones were erected to commemorate his valour.’

Indefatigable hard core hands-on researcher Sadashiv Tetvilkar, who already has seven books to his credit, has now published Maharashtratil Veergal (Hero Stones of Maharashtra), which highlights the enormous potential of these memorial stones as unique, unconventional sources of local history, in combination with the rich and varied oral traditions of the region. Together with the more conventional methods of decoding historical evidence, such as texts, the book is a significant addition to the armoury of historians and archaeologists working on the early mediaeval past of Maharashtra.

These Hero Stones, often found together with Sati Stones erected to honour wives who committed sati after the husband’s death at the battlefield, are unequivocally the memorials erected to commemorate heroes who valiantly fought and died on the battlefield while defending and protecting the lives and properties of the communities they belonged to, from wild predators or human invaders. It is a humble and affectionate tribute paid by the commoners to their brave hero, so as to inspire future generations to follow in his footsteps.

These Hero Stones, often found together with Sati Stones erected to honour wives who committed sati after the husband’s death at the battlefield, are unequivocally the memorials erected to commemorate heroes who valiantly fought and died on the battlefield while defending and protecting the lives and properties of the communities they belonged to, from wild predators or human invaders. It is a humble and affectionate tribute paid by the commoners to their brave hero, so as to inspire future generations to follow in his footsteps.

What makes this effort significant is that this study fills up a huge gap in reconstructing local history, long felt but left unaddressed due to neglect and apathy. Part of the challenge lies in the fact that there is rarely, if ever, any inscription on the Hero Stones, and they are lying open to the skies, which makes it difficult to establish their context in time and space.

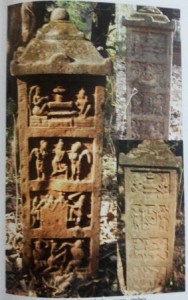

The book is embellished with colour and B&W photographs of outstanding samples of Hero Stones. Although the author insists that the Veergals included in his book are only a compilation of the possible sources, it has nevertheless opened floodgates of an exciting archaeological and ethnographic adventure that will unfold unseen aspects of early medieval history of Maharashtra.

Tetvilkar points out that Hero Stones are not unique to Maharashtra: they are found in great numbers in Karnataka, Goa, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Kashmir, Andhra, Himachal, Bengal and Gujarat, which highlights the cultural unity of India at the very grassroots. Hero Stones are rectangular slabs of hard stone, usually with three vertical panels decorated with low relief sculpture which is a continuous narrative of valour, sacrifice and magnanimity, through a battle scene, death and ascent into heaven. The sun and moon at the top indicates that the fame of the hero would remain undiminished forever.

Tetvilkar holds the view that some of these local heroes were eventually elevated to the status of gods and came to be worshipped by villagers, which explains the large number of local deities venerated in rural Maharashtra. The attributes of these heroes/gods and the myths and legends associated with them give us important insights into the lives, values and aspirations of the communities they belonged to. They also give us significant clues into the process of Aryanisation of the hinterland and the commingling of varied cultural traits and tradition. By enhancing the credibility of myths and folklore, they constitute a textbook of history from below.

Although Veergals have been known in India from the 2nd to the 18th centuries, a deep study has surprisingly been largely absent. Tetvilkar points out the contribution made to this field by famous anthropologist Gunther Sontheimer and strive to complete the job he left unfinished. The book is an outcome of the relentless energy with which he roamed over jungles and mountains, undeterred by heat or cold or rains, speaking to elders in the villages, gathering and classifying data and correlating this data with the published works of scholars.

Tetvilkar gives several examples of eye-witness accounts of the British who saw women voluntarily committing Sati after the death of their husbands at the battlefield, and the  courage and quiet dignity with which these women embraced a painful death, which has been immortalised on the Sati Stones. Women have also been shown on horseback, or worshipping a Shivalinga along with their husbands after reaching heaven. A few Sati Stones also show the woman being coerced into following the Sati custom, and Tetvilkar analyses how Sati is Bengal was different from what it was in Maharashtra, and why Bengal was at the forefront of resistance to the custom.

courage and quiet dignity with which these women embraced a painful death, which has been immortalised on the Sati Stones. Women have also been shown on horseback, or worshipping a Shivalinga along with their husbands after reaching heaven. A few Sati Stones also show the woman being coerced into following the Sati custom, and Tetvilkar analyses how Sati is Bengal was different from what it was in Maharashtra, and why Bengal was at the forefront of resistance to the custom.

At Degaon in Raigad district is a Hero Stone showing a ten headed enemy, but Ram, Seeta, Lakshman and Hanuman are absent. Blood from the severed fingers of the enemy is shown dripping over a Shivalinga placed below. Tetvilkar dates this Veergal to Shivaji’s times on account of the similarities with the known event in Shivaji’s life.

(Pictures courtesy Shubha Khandekar)