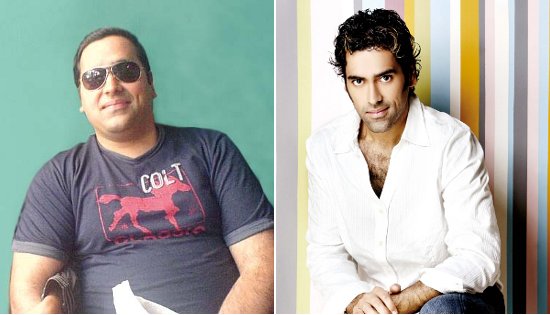

Artist, free hand painter Ranjit Dahiya is bringing Bollywood alive in Mumbai for a year, one wall at a time.

by Vrushali Lad | vrushali@themetrognome.in

Ranjit Dahiya is 33, charming and quite direct. He pays full attention when you’re speaking, is disarmingly honest, and wears his small town origins with enviable confidence. “I come from a small village in Haryana, and I didn’t know what the hell I was going to do as a young boy,” he remembers. “Art happened to me because it was an avenue that I decided to explore on a whim. I didn’t know any English, I didn’t know what art was supposed to be.” And yet, he graduated from National Institute of Design (NID) Delhi and holds a Fine Arts degree from a Chandigarh college – but everything’s come with a bit of a struggle.

Today, Ranjit is celebrated as an artist, especially since he founded and started the Bollywood Art Project (BAP), a community visual art project under which he hand paints popular people and moments in Hindi cinema on walls that are located in public spaces. He stays at Bandra and has also worked on walls in this suburb, though he is looking at ‘good walls’ in other places as well. “I came to Mumbai in 2008 because I got a job as a graphic designer with a website here,” he says. “I had just passed from NID. When I came to Mumbai, I realised that there were not enough art installations or paintings in the city. So I became very interested with The Wall Project, and met up with them to understand what they were doing.”

Today, Ranjit is celebrated as an artist, especially since he founded and started the Bollywood Art Project (BAP), a community visual art project under which he hand paints popular people and moments in Hindi cinema on walls that are located in public spaces. He stays at Bandra and has also worked on walls in this suburb, though he is looking at ‘good walls’ in other places as well. “I came to Mumbai in 2008 because I got a job as a graphic designer with a website here,” he says. “I had just passed from NID. When I came to Mumbai, I realised that there were not enough art installations or paintings in the city. So I became very interested with The Wall Project, and met up with them to understand what they were doing.”

Through the Wall Project, Ranjit got the chance to visit Paris and later, Le Rochelle, both times to paint Bollywood-themed canvases. “I painted at 12′ x 32′ poster of Amitabh Bachchan at Paris, and I finished it in four days. The greatest moment for me was when Mr Bachchan himself arrived at the fest and congratulated me on my work – I have always been a great fan!” he beams.

His two trips made him realise that people abroad really loved Bollywood. “They like the style, the culture, the drama. This year, I started the BAP because I wanted to celebrate the spirit of Bollywood in my own way, in the city that I live in,” he explains.

Childhood scenes

Ranjit’s parents, both employed with the Government, expectedly wanted him to get an education and a stable job, but he flunked his college exams and his father told him to go tend to the fields that the family owned. “I actually loved going to the fields,” he smiles. “But my father wondered what I would do with my life. Then a relative once met me and said that I could learn how to whitewash walls from him. Soon, I was working with different contractors and whitewashing walls; for each job, I would get Rs 40.”

A few months later, he met a school friend who was studying to be an engineer. “He asked me what I was doing, and was stunned  with my answer. He asked me if I had heard of Fine Arts. I said I hadn’t, and the conversation was promptly forgotten,” he says. At the time, the local school wanted a Saraswati painting done in its premises, and Ranjit volunteered. “People said, ‘What do you know about painting?’, but I had always loved drawing and painting, even when I was very young. I did a 6′ x 4′ Saraswati painting on a wall, and everybody liked it,” he remembers.

with my answer. He asked me if I had heard of Fine Arts. I said I hadn’t, and the conversation was promptly forgotten,” he says. At the time, the local school wanted a Saraswati painting done in its premises, and Ranjit volunteered. “People said, ‘What do you know about painting?’, but I had always loved drawing and painting, even when I was very young. I did a 6′ x 4′ Saraswati painting on a wall, and everybody liked it,” he remembers.

Spurred by this, he decided to visit a relative in Panipat, who promised to teach him how to write with paints and do other paint work. “I sat for my failed college year during this time, and returned after a year to apprentice with a local painter. You know, doing ‘Mera gaon, mera desh‘ kind of stuff. Then one day I remembered my friend and that he’d said something about Fine Art. I decided to check it out,” he says. After obtaining some basic information on Fine Art courses, I sat for and passed the entrance exam and got admission to a college in Chandigarh.”

“I was the small town boy from the village, I didn’t know what ‘art’ was, and my medium of instruction was Hindi,” he remembers. “It was tough, but I slowly got the hang of it. In my fourth year, I heard of this place called NID (National Institute of Design), and I asked a senior, ‘Sir, what is NID?’ His prompt reply was, ‘Forget it, you can never go there,'” Ranjit chuckles.

Adamant to get into NID, he sat for their entrance exam and failed spectacularly. “My lack of English had let me down. I wondered what to do next, getting really confused about several available options. Finally, I burnt all the college prospectuses I had gathered, and reapplied to NID.” In the meantime, however, he put in a solid year of English learning. “I would read the newspapers and whichever books I could find. Soon, I began to understand the language, at least enough to know what was being said. I had flunked the entrance exam because I hadn’t understood the questions,” he says.

The NID life

The next time he appeared for the NID exam, he understood the questions, though his English was still questionable. “I cleared the exam, but I continued to flounder in the course because I had no idea about art. Finally, the faculty asked me to withdraw from the programme, because I didn’t have the required aesthetics and depth, or to take an extra year on my Foundation Course. I chose the latter option,” he says.

After spending over two years in one batch and submitting a live project comprising a 206-page document in English, plus an ‘identity’ for a museum in Pune, Ranjit was convocated in 2007. This year, he started the BAP “out of passion”. He says, “The best thing about BAP was that it helped me get back to painting. I had been working full time, but a job makes me complacent. So I take up freelance work and I founded by own company, Digital Moustache.”

The Bollywood connect

“I’ve always loved Bollywood films, and when I was very young, I’d painted a gate with the face of a hero from a film magazine,”  he remembers. “I hadn’t realised that the connect with films was so strong, strong enough for me to want to be associated with Bollywood in some capacity. Cinema builds our culture and perceptions, and it is a record of our lives and the times we live in. I am enjoying the BAP because I love Bollywood,” he explains.

he remembers. “I hadn’t realised that the connect with films was so strong, strong enough for me to want to be associated with Bollywood in some capacity. Cinema builds our culture and perceptions, and it is a record of our lives and the times we live in. I am enjoying the BAP because I love Bollywood,” he explains.

His dream is to revive the Bollywood posters industry, and he is currently scouting for the best wall to paint yesteryear dancer and actor Helen on. “Many people criticise my work, saying that what I do is just copy from somewhere, there is no originality. I don’t care about all of this as long as I am enjoying my work. There are a lot more people who are enjoying my work, and their appreciation gives me a real high,” he grins.