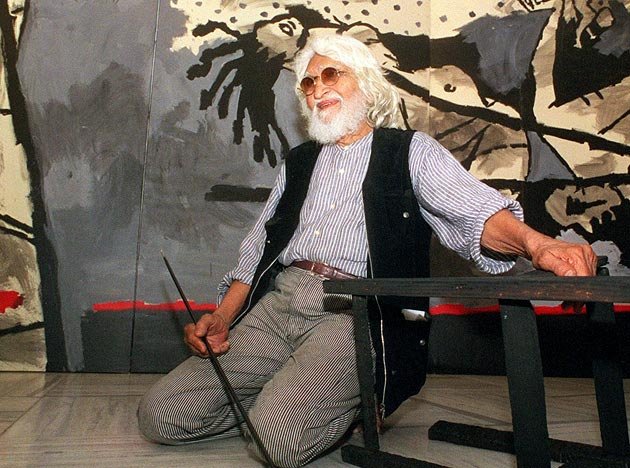

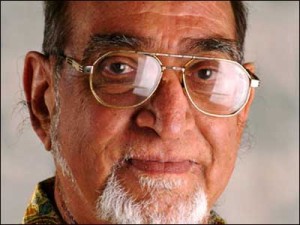

An encounter with MF Husain before he made Meenaxi showed the artist’s love for women and his passion for films.

by Humra Quraishi

I last met MF Husainsaab here in New Delhi, during one of those crucial junctures in his life and times – his art works had been attacked by right-wing goons and he had also been talking about his deep passion for films; filmmaking, to be precise.

When I tried asking him for his reactions to those attacks on his art work, he tried fobbing me off, waving his hands and mumbling impatiently, “Kuchh bhi chalta hai…theek hai…” He didn’t want to comment on the matter or be drawn into further controversy. With that, I changed my questions, and diverted him towards his latest passion – film-making.

When I tried asking him for his reactions to those attacks on his art work, he tried fobbing me off, waving his hands and mumbling impatiently, “Kuchh bhi chalta hai…theek hai…” He didn’t want to comment on the matter or be drawn into further controversy. With that, I changed my questions, and diverted him towards his latest passion – film-making.

With the very mention of films, he relaxed and became quite forthcoming. “Film-making is my passion, and now I plan to make a comedy. (It’s) A lot of work, but anyway, I am not a lazy man. I work day and night. Yes, I work all through…get very little sleep.”

But can a comedy be a success, I asked.

He looked upset. “I’m planning to make a subtle comedy which will be a part of our culture. It’s a misconception, brought about by the media, that our people can’t appreciate comedy. I would say with great confidence that 80 per cent of the people in rural India do know and can appreciate comedy and those different aspects to our culture. Our people can sense and appreciate so much, because of our culture that is part of our very being, of our everyday life and living… It’s the elite living in big cities who are ignorant.”

But aren’t our rural folks more engrossed with their daily battles for survival? With that in the background, can they afford the luxury of watching films, I wondered.

He was annoyed, to say the least. “What sort of questions do you media people ask me these days? Some of you ask me about Madhuri (Dixit)! Now you are asking all this! Talk to me  about this latest film I’ve made. No, not a commercial venture for me, my latest film – Meenaxi: A Tale of 3 Cities. It has been my passion to make this film on this subject…I have shot it in three different cities; Prague, Hyderabad and Jaisalmer.

about this latest film I’ve made. No, not a commercial venture for me, my latest film – Meenaxi: A Tale of 3 Cities. It has been my passion to make this film on this subject…I have shot it in three different cities; Prague, Hyderabad and Jaisalmer.

“The story revolves around this woman searching for love and this restless writer…the bond that is forged between them. See this film and you will know what I have tried to portray, that bond between the two souls. No, it isn’t a commercial venture for me, I just made it because I wanted to.”

I cautiously put in a question: “What about the distractions in your life?”

“What distractions? Here I’m working din aur raat, what distractions are you talking about?”

“Now that you are making films, so actresses and other women could attract or distract you…” I said.

“Show me one man who isn’t attracted to women. Let there be one thousand women and I can make each one of them happy! It’s all a matter or rapport.”

What attracts you in a woman, I asked.

“I’m attracted to strong women…those independent types and definitely NOT the weak types. I find those weak, crumbling type of women just hopeless. In fact, the women in my paintings are inspired by the Shakti in a woman. I believe that our traditional Indian women carry a special strength. It’s that strength which can be termed magical and it can do wonders,” he said.

“I’m attracted to strong women…those independent types and definitely NOT the weak types. I find those weak, crumbling type of women just hopeless. In fact, the women in my paintings are inspired by the Shakti in a woman. I believe that our traditional Indian women carry a special strength. It’s that strength which can be termed magical and it can do wonders,” he said.

I had been studying his latest series of paintings on women; a combination of the Gupta Period and the folk form. He was more than happy to explain the details of his Tribhanga Series. “There’s an emphasis on the head, the shoulders and the hips of the woman. The way an Indian woman walks is so graceful, I love it! If you’ve noticed, the Western woman walks straight, without a sway, and the walk loses its appeal. Even Kalidas had written on the woman’s gait and he had compared it to the graceful walk of an elephant, calling her Gajagamini (she who walks with the languorous grace of an elephant).

“I am also attracted to a woman’s ear lobe, the very turn of her head, the movements of her hand. Actually, once you are in love, then everything about her attracts you…”

Have you been in love, I asked.

“I have admired many and loved several women,” he said at once.

“But doesn’t true love happen just once in a lifetime?” I persisted.

“Yes, it’s true, but the same love keeps shifting from person to person, from one woman to another.” Perhaps in response to my bewildered look on hearing this terribly strange, yet practical rationale on love, he burst into poetry:

‘Ek mere muhabbat ka itna sa fasana hai /

Simtai toh dil ashak /

Phailai to zamana hai…’

He was suddenly in the mood to talk further on this subject. “I love the naïve type of woman. She leaves a definite impression. But she should be naïve and yet strong.”

“But isn’t that a strange combination? Naïve and strong?” I said.

“Then have two women!” he joked.

I had to ask him: “You are married, with children and grandchildren. With that in the background, didn’t you face problems falling in love/sustaining a love affair?”

“Nothing matters once you are in love,” he said. “Once a rapport is built, then nothing comes in the way…”

Then he gave me a sidelong glance and mumbled, “Par aap se woh rapport nahin ban pa rahi hai…(I am not able to build a rapport with you).”

“Thank God for that!” I retorted. “I don’t want any rapport with you.”

Humra Quraishi is a senior journalist based in Gurgaon. She writes on politics, social issues and occasionally, on films. Cinema@100 is a series that celebrates 100 years of Indian cinema.

(Pictures courtesy vakkomsen.blogspot.com, realandfun.blogspot.com, quicktake.wordpress.com, cmaconline.org, starmusiq.com)