One was a liberal academic, the other was a feted Hindi film actor, but their lives were really quite similar.

by Humra Quraishi

by Humra Quraishi

The passing away of Dr Asghar Ali Engineer recently saddened me, to say the least. Though I had met the scholar and academic several times in New Delhi and also in Sringar, I had met him just once in Mumbai. I was determined to catch up with him in Mumbai, because I have been to that city just once in my life and I wanted to meet him during that visit.

This was in the winter of 2006. From Colaba, I made my way to Dr Engineer’s Santacruz office, and it was lunch time when I got there. We spoke over lunch; his lunch, he said, was home-cooked and prepared by his daughter-in-law, who is a Maharashtrian. It was a simple spread – not the expected kormas or kababs or biryani, but two plain rotis, curd, curry, aloo gobi sabzi and some khichdi.

He spoke frankly of present-day realities. “Today, the government has to prioritise justice and security. I must emphasise that no Muslim group or individual wants to take revenge, even after the Gujarat pogrom. I have been talking to people, and everyone realises and knows that confrontation policies do not work, only healthy co-existence does. I have been going to Gujarat and talking to Muslims. They have been saying that all they want is security, so that they can live in peace. They’re worried about their lives, their livelihood, their children…”

He also said, “Our focus should be on how to clear those myths about Muslims. I’m trying my best to clear these myths by holding  workshops for the police, for college and school students. It’s only through dialogue that many misconceptions about Muslims can be cleared.”

workshops for the police, for college and school students. It’s only through dialogue that many misconceptions about Muslims can be cleared.”

I have read some really excellent research he had done on the communal riots. That afternoon, as he detailed and traced the history and potential of communal politics, it became apparent that it had peaked in the aftermath of the Babri Masjid’s razing.

Dr Asghar Ali Engineer always spoke calmly, with all the facts at hand. Probably this was what helped him reach out to so many people.

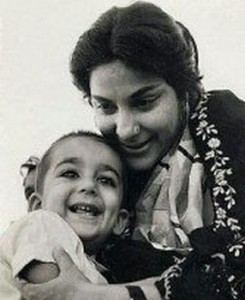

With Sanjay Dutt going to prison, I have been reading this essay by writer Khushwant Singh on Nargis Dutt, Sanjay’s mother. I quote, “Nargis Dutt was introduced to me through the then editor of Femina, Gulshan Ewing. I’d seen her film Mother India, and I had met her when they (the Dutts) were not doing too well, and she had almost retired from films. She told me that two of her children were studying at the Sanawar School, not far from my home in Kasauli, and she asked if she could stay at my Kasauli cottage during the Sanawar Founders’ Week. With that I’d quipped, ‘Only on one condition, and the condition is that I have your permission to tell everyone that Nargis slept in my bed!’

With Sanjay Dutt going to prison, I have been reading this essay by writer Khushwant Singh on Nargis Dutt, Sanjay’s mother. I quote, “Nargis Dutt was introduced to me through the then editor of Femina, Gulshan Ewing. I’d seen her film Mother India, and I had met her when they (the Dutts) were not doing too well, and she had almost retired from films. She told me that two of her children were studying at the Sanawar School, not far from my home in Kasauli, and she asked if she could stay at my Kasauli cottage during the Sanawar Founders’ Week. With that I’d quipped, ‘Only on one condition, and the condition is that I have your permission to tell everyone that Nargis slept in my bed!’

She had a great sense of humour and laughed heartily on hearing this. Years later, when we were both nominated to the Rajya Sabha and given seats next to each other and whenever anyone tried to introduce us, she would say, ‘You don’t have to introduce us. I have slept in his bed.’

“…One thing that intrigued me was her (Nargis Dutt’s faith. Was she a Muslim or Hindu or both or nothing? She wore a bindi on her forehead, married a Brahmin, gave her children Hindu names and was often seen at Swami Muktanand’s ashram at Ganeshpuri. Nevertheless, she was buried with Muslim rites in a Muslim graveyard with her husband reciting the fateha. I can’t think of any Indian family which better exemplified the principle of Sarva Dharma Samabhav.”

Humra Quraishi is a senior journalist based in Gurgaon. She is the author of Kashmir: The Untold Story and co-author of Simply Khushwant.

(Pictures courtesy www.news24online.com, sitagita.com, www.hindu.com)