A new book on the ancient Indian ‘shringara’ tradition brings to mind all that’s best in our beautiful country.

by Humra Quraishi

by Humra Quraishi

I believe that our lives in the good old days were simple and good for our overall psyche. Those ways should be brought back. Our food and lifestyle, our ideas of beauty, even the very fabric we chose to wear next to our skins jelled with the climate and our living conditions.

Cottons and khadi are apt for our summers and the humidity, yet we ditch them for synthetics and polyesters. This brings to mind an incident, several years ago, when Delhi- based art historian Jyotindra Jain had gone to meet writer Mulk Raj Anand. The first thing that the writer did was to send Jain to the nearest Gandhi Ashram so that the latter could change his clothes – his trousers and synthetic shirt – and slip into a more comfortable and suitable khadi kurta pyjama!

Another thing to bring to mind my present preoccupation (for this column) with healthy living and beauty, was writer Alka Pande’s  recently published book, Shringara – The Many Faces Of Indian Beauty.

recently published book, Shringara – The Many Faces Of Indian Beauty.

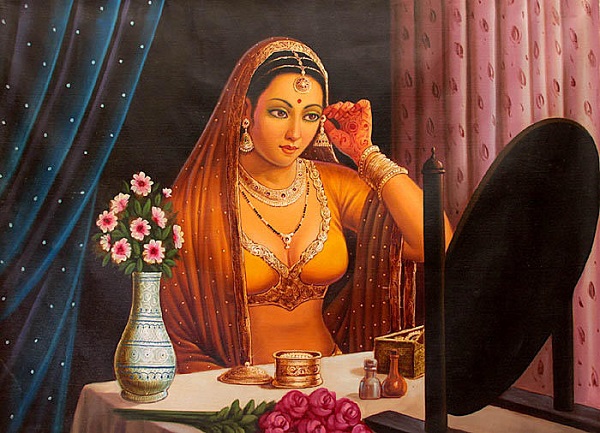

Right on the front cover is this overwhelming photograph of Indian woman clad in ethnic clothes, while the back cover has a woman from a bygone era getting her somewhat bare body massaged; she is in a semi-Kamasutra pose, but as you sift through the pages, you understand that the underlying theme is shringara. The book takes you through shringara in verse, paintings, architecture, form and figure.

As Pande elaborates, “As an art historian, I’m often asked to define beauty in a word, phrase or even as a concept. I see beauty essentially as a value connected to the perception of different alternative aspects of human emotionality. When we perceive something that is in harmony with nature and generates a feeling of joy and pleasure within us, we describe it to be beautiful…”

She adds, “Today, the cultural diversity of India faces the pulls and pressures of tradition and modernity, rural and urban, folk and classical, and most importantly, local and global. Shringara, too, faces the challenges of perception, where the beauty of adornment and the beauty of ugliness are two sides of the same coin…this is a time to ask important questions on the concept of beauty: Has the morphology of the old nayika been given up for more westernised perceptions? Has there been an Indian renaissance, apart from path-breaking initiatives of AK Coomaraswamy and Rabindranath Tagore? Who are the new patrons of Indian art?”

She adds, “Today, the cultural diversity of India faces the pulls and pressures of tradition and modernity, rural and urban, folk and classical, and most importantly, local and global. Shringara, too, faces the challenges of perception, where the beauty of adornment and the beauty of ugliness are two sides of the same coin…this is a time to ask important questions on the concept of beauty: Has the morphology of the old nayika been given up for more westernised perceptions? Has there been an Indian renaissance, apart from path-breaking initiatives of AK Coomaraswamy and Rabindranath Tagore? Who are the new patrons of Indian art?”

What I took away from this book was not just the easy flow of words, but also the pictures and graphics that merged seamlessly with the narrative. It nudged me to introspect, perceive more, think of all that’s beautiful in our land.

(Pictures courtesy alkapande.com, www.exoticindia.com)