Devendra Desai is a 66-year-old, toy-crazy man! No child can be left without a game or toy if he’s around.

by Vrushali Lad | vrushali@themetrognome.in

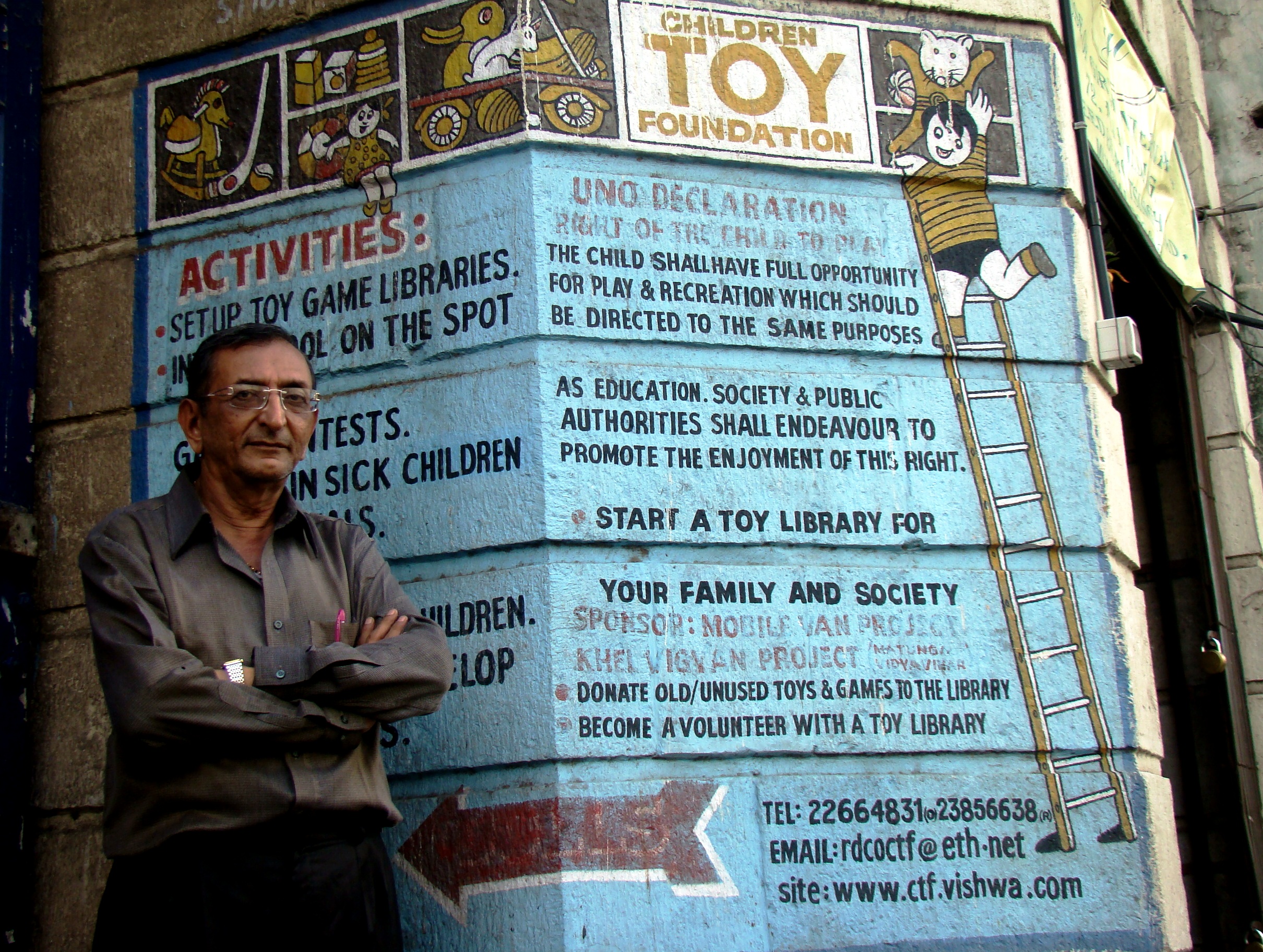

Devendra Desai runs a decrepit paper firm, and you wouldn’t even notice the little place if you were to walk past it. But several people stop and read what he’s painted on the wall leading to his office at Fort – Children Toy Foundation – with a list of what the place does. Intrigued by the words, several people walk in and ask what it’s all about.

“That board has been really lucky for us,” chuckles Devendra (66), who has been running the Foundation since 1982. “So many people have come in and asked for details, so many more have donated toys. I even got my first overseas donor through this board.”

But what really goes on inside? What appears to be just a hole in the wall at first, houses some of the most astonishing games and puzzles. Every available surface is stacked high with board games, most of them with names most people haven’t even heard of, while he’s put up paper charts of mathematical puzzles on one of the overhead cabinets. During the course of our conversation, it becomes clear just how priceless some of the games in his collection are, especially ‘Chess 64’ (pictured), a customised game (that he created with a friend, Arun Mehta) which has an astounding 64 games rolled inside one pack of playing cards. “We tried to market this game, but it didn’t take off because you needed a lot of time to explain it. But I am thinking of bringing it out again,” he muses.

But what really goes on inside? What appears to be just a hole in the wall at first, houses some of the most astonishing games and puzzles. Every available surface is stacked high with board games, most of them with names most people haven’t even heard of, while he’s put up paper charts of mathematical puzzles on one of the overhead cabinets. During the course of our conversation, it becomes clear just how priceless some of the games in his collection are, especially ‘Chess 64’ (pictured), a customised game (that he created with a friend, Arun Mehta) which has an astounding 64 games rolled inside one pack of playing cards. “We tried to market this game, but it didn’t take off because you needed a lot of time to explain it. But I am thinking of bringing it out again,” he muses.

“Even as a child, I had decided that I wouldn’t do the usual ‘study-get a job-get married’ routine,” Devendra remembers. “I bet my older sister, when I was 16 years old, that I would never marry. I had been an avid chess player, and I loved puzzles and mathematical problems. I started solving chess problems regularly – in those days, there used to be a space titled ‘Ramji’s Crossword Corner’ in The Times of India, which featured chess problems, and I loved to crack those.”

But it was a chance meeting with Manilal Dund, who was running the Chacha Nehru Toy Library in Bandra in the 1970s that set the course for Devendra’s life. “I had been helping in the family paper business, but I was more interested in social work. I had put in time at Vinoba Bhave’s ashram, I had even been part of the Cow Slaughter Satyagraha in 1981. But this fellow came to see me about an order for paper. While talking, he told me about this toy library that he was running, and I told him that I was interested in working with him,” Devendra says. The obsession with games had already gripped him, however – he even used to play on the local train. “I used to play Naughty Packs (a variation on Brainvita) on the train. When others would peep into my game and suggest ways to crack it, I would ask them to participate. Sometimes, I even sold packs on the train.”

In 1982, Devendra had found others who shared his passion for games and his vision for a toy library for children, and he started the Children Toy Foundation (CTF) that year. Manilal Dund was also a part of this team. “The idea was to make toys accessible to children who did not have access to them. Every child has the right to play, and the CTF was founded on this belief,” he says. “I would go to schools, asking them for a room to spare for toys. But several schools did not have enough space for their own classrooms, so that idea fizzled out.”

Meanwhile, Devendra would find new games and test them, coming up with variations of one game to maximise its utility. “There was a boy, a street dweller, who used to peep in and watch me while I played games at my office. His presence disturbed me, so I told him to come to play any time between four and six pm. Later, he started bringing his friends as well. At one time, there would be about 30 children inside the office, and about 20 more on the pavement outside, all of them playing games!” he laughs.

Devendra started his first toy library at Prarthana Samaj, near his place of residence, in 1984. “It was featured on TV, and the next day, there was a line of parents wanting to take toys home for their children.” The model was simple – children could borrow toys for a certain time, then return it and play with something else. “But I wanted to reach more children, and for this, I needed a van to take the toys to areas where children could play with our toys. Luckily for me, a journalist from the Economic Times came to interview me, and I said to him, ‘You journalists are useless. I need a van, but you have no idea how to help me.’ He put in the details of the CTF and our requirement in the ‘Good Samaritan’ section of the paper, and very soon, a kind donor responded to the write up and helped us with a van in 1998.”

The media and donors alike have been very kind to the FoundationCTF, Devendra says, helping him in direct and indirect ways to get funding and whatever else he needed to keep the Foundation growing. “Till date, we have helped set up over 292 toy libraries all over India. So many more have started using our model. We started the Khelvigyan centre (that combines entertainment and education via games) in City of Los Angeles municipal school in 2001 where we have a permanent room of over 700 toys and games that pre-primary and primary children can play with twice a week free of cost, during school hours.”

It is to the CTF’s eternal credit that they have a permanent centre inside Arthur Road Jail, for the children of female inmates. Yerawada Jail wanted the same model, so CTF helped set up a centre there as well. Besides municipal schools all over the country, the CTF has also reached 12 remote villages in Allahabad, there about 7,000 children avail of the toys and games.

“It has been scientifically proved that play is integral to children’s overall development. We only hope that more schools will include a play hour with puzzles, toys and games in their curriculum, all over the country,” Devendra says. “Why only children, even adults should play. We have forgotten to play and hence, we have forgotten how well we can socialise with others over a game. There are so many games freely available in the market, but we must make the effort to go out and look for them. Slowly, people are realising the importance of toys in children’s development.”

As if on cue, Samita Shah, who lives in the area, stops by to drop off a brand new scooter. “It just needs to be assembled. My son had two scooters, so I decided to drop one off. All my friends also regularly donate toys to Mr Desai. I think his work is brilliant,” she smiles.

Devendra simply looks back at me and grins.

The Children Toy Foundation is at 76, Ali Building, Shahid Bhagat Singh road, Fort, Mumbai.