How do you know if your loved one is suffering from dementia or Alzheimer’s? Use this checklist to know more.

Dementia is a general term to denote a progressive degenerative disease of the brain resulting in loss of memory, intellectual decline, behavioural and personality changes. Mostly older people above 60 years of age are affected by this condition. In Latin, ‘dementia’ means irrationality, and this disorder results in a restriction of daily activities, and in most cases, leads in the long term to the need for care. There are many forms of dementia, the most common one being Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s knows no social, economic, ethnic or geographical boundaries and affects people throughout the world. It is estimated that every seventh person in world will suffer from some form of dementia.

Alzheimer’s knows no social, economic, ethnic or geographical boundaries and affects people throughout the world. It is estimated that every seventh person in world will suffer from some form of dementia.

There is no cure for the disease, but some treatment and therapy is available to stabilise and arrest the progress of the disease. Here’s what you should watch out for if you think a loved one may be suffering from dementia or Alzheimer’s, and what is normal behaviour:

#1) Memory loss that disrupts daily life

One of the most common signs of Alzheimer’s is memory loss, especially forgetting recently learned information. Others include forgetting important dates or events; asking for the same information over and over; relying on memory aides (such as reminder notes or electronic devices) or family members for things they used to handle on their own.

What’s typical? Sometimes forgetting names or appointments, but remembering them later.

#2) Challenges in planning or solving problems

Some people may experience changes in their ability to develop and follow a plan or work with numbers. They may have trouble following a familiar recipe or keeping track of monthly bills. They may have difficulty concentrating and take much longer to do things than they did before.

What’s typical? Making occasional errors when balancing a checkbook.

#3) Difficulty completing familiar tasks at home, at work or at leisure

People with Alzheimer’s often find it hard to complete daily tasks. Sometimes, people may have trouble driving to a familiar location, managing a budget at work or remembering the  rules of a favourite game.

rules of a favourite game.

What’s typical? Occasionally needing help to use the settings on a microwave or to record a television show.

#4) Confusion/disorientation with time or place

People with Alzheimer’s can lose track of dates, seasons and the passage of time. They may have trouble understanding something if it is not happening immediately. Sometimes they may forget where they are or how they got there.

What’s typical? Getting confused about the day of the week but figuring it out later.

#5) Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships

For some people, having vision problems is a sign of Alzheimer’s. They may have difficulty reading, judging distance and determining colour or contrast. In terms of perception, they may pass a mirror and think someone else is in the room. They may not realise they are the person in the mirror.

What’s typical? Vision changes related to cataracts.

#6) New problems with words in speaking or writing or problems with language

People with Alzheimer’s may have trouble following or joining a conversation. They may stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue or they may repeat themselves. They may struggle with vocabulary, have problems finding the right word or call things by the wrong name (e.g., calling a “watch” a “hand-clock”).

What’s typical? Sometimes having trouble finding the right word.

#7) Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps

A person with Alzheimer’s disease may put things in unusual places. They may lose things and be unable to go back over their steps to find them again. Sometimes, they may accuse others of stealing. This may occur more frequently over time.

What’s typical? Misplacing things from time to time, such as a pair of glasses or the remote control.

#8) Decreased or poor judgment

#8) Decreased or poor judgment

People with Alzheimer’s may experience changes in judgment or decision-making. For example, they may use poor judgment when dealing with money, giving large amounts to telemarketers. They may pay less attention to grooming or keeping themselves clean.

What’s typical? Making a bad decision once in a while.

#9) Withdrawal from work or social activities/loss of initiative

A person with Alzheimer’s may start to remove themselves from hobbies, social activities, work projects or sports. They may have trouble keeping up with a favourite sports team or remembering how to complete a favourite hobby. They may also avoid being social because of the changes they have experienced.

What’s typical? Sometimes feeling weary of work, family and social obligations.

#10) Changes in mood and personality

The mood and personalities of people with Alzheimer’s can change. They can become confused, suspicious, depressed, fearful or anxious. They may be easily upset at home, at work, with friends or in places where they are out of their comfort zone.

What’s typical? Developing very specific ways of doing things and becoming irritable when a routine is disrupted.

The Metrognome is committed to the cause of Alzheimer’s and dementia awareness through all of September 2013. If you want to share information or anecdotes related to Alzheimer’s or dementia, write to editor@themetrognome.in and we will feature it.

(Pictures courtesy www.webicina.com, www.firstpost.com, www.thehindu.com, www.indianexpress.com)

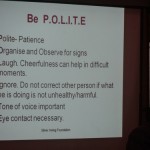

assisted elder care facility at Nala Sopara. The facility, A1 Snehanjali, held an interactive talk and play, played an interactive PPT and showed an inspiring video.

assisted elder care facility at Nala Sopara. The facility, A1 Snehanjali, held an interactive talk and play, played an interactive PPT and showed an inspiring video. “A total of 55 people participated from various churches, senior citizens associations, women’s NGO Sakhaya, students from Nirmala Niketan College of Social work and residents and staff of A1 Snehanjali. Interestingly, the programme was inaugurated by chief guest corporator Rajan Nayak of Vasai Virar Municipal Corporation,” said Sailesh Mishra, Founder, Silver Innings.

“A total of 55 people participated from various churches, senior citizens associations, women’s NGO Sakhaya, students from Nirmala Niketan College of Social work and residents and staff of A1 Snehanjali. Interestingly, the programme was inaugurated by chief guest corporator Rajan Nayak of Vasai Virar Municipal Corporation,” said Sailesh Mishra, Founder, Silver Innings.