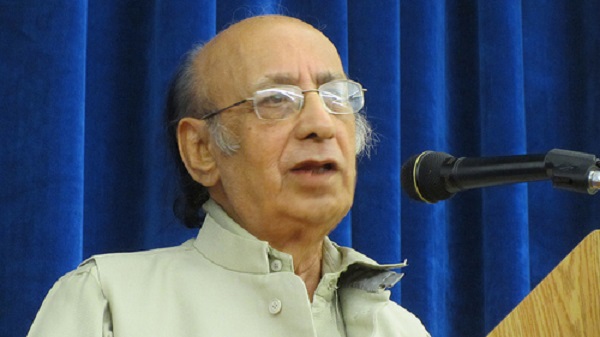

Nida Fazli, Urdu poet and lyricist, speaks on why he made Bombay his home despite his family moving to Pakistan.

by Humra Quraishi

When I’m feeling utterly hopeless about life, I say these lines by poet Nida Fazli to myself –

‘Just keep on living /

Just keep on living like this /

Say nothing /

When you get up in the morning /

Take a head count of the family /

Slouch in the chair and read the paper /

There was a famine there /

And a war raged somewhere else /

Be thankful that you are safe/

Switch on the radio and listen to the new pop songs /

When you leave the house /

Paste a smile on your face/

Pack handshakes in your hands /

Keep a few meaningless phrases on your lips /

Be passed through different hands like a coin/

Say nothing /

A white -collar /

Social respect /

A few drinks everyday/

What else do you need /

Just keep on like this /

Say nothing …’

And as I say these lines to myself, I recollect the two occasions I had the chance to meet the legendary poet and film lyricist in New Delhi. I had long conversations with him about his poetic journey to how he started writing lyrics for Hindi films.

And as I say these lines to myself, I recollect the two occasions I had the chance to meet the legendary poet and film lyricist in New Delhi. I had long conversations with him about his poetic journey to how he started writing lyrics for Hindi films.

I had had no idea that his journey had begun on a rather tragic note.

Around the time of the Partition of India and Pakistan, he had been engaged to be married. The Partition played havoc with this plan, when his own family and that of his fiancee migrated to the newly-carved country, Pakistan. “I did not move from Hindustan,” Nida told me. “I did not want to. So I was left back all alone.” He confessed to facing very trying times after this, having to brave several testing incidents for a long time. He moved to Bombay for work in 1964, and after an initial period of struggle, his talents as a poet began to be noticed in the film industry. His big break, however, came when filmmaker Kamal Amrohi hired him to finish the songs on his much-delayed magnum opus, Pakeezah. Fazli was brought in as a replacement for Jaan Nisar Akhtar, who had died before finishing two songs.

But Bombay brought the much-needed calm in his life. So how did he get from Uttar Pradesh to Bombay? “I was okay with moving to Bombay and I have always felt absolutely at home there,” he explaind. I found out, during the course of our conversation, that we came from the same qasba in UP, and as talk veered to our ancestral homes and the lives we used to live,

I was struck by how comfortable he was not speaking about films and the glitzy world of cinema, which had obviously not had enough of him yet – this year he was conferred the Padma  Shri by the Indian Government – despite him retaining his poet’s identity and not getting it mixed up with that of a film lyricist’s.

Shri by the Indian Government – despite him retaining his poet’s identity and not getting it mixed up with that of a film lyricist’s.

After a long chat, it was time to say khuda hafiz. But I still had one unanswered question. After his failed attempt at marriage, when his fiancee moved to another country, how did he settle in his personal life?

“Well, I found a companion in Bombay,” he smiled. “I married her and I have settled in this city for ever.”

“It is said that in Mumbai these days, even the big names in Bollywood who are Muslims are finding it difficult to buy or rent an apartment. Did you face any such situation?” I asked.

“No, I haven’t,” he said at once. “But this could be because my partner is a non-Muslim.”

Watch the ghazal ‘Hoshwalon ko khabar kya’ from Sarfarosh, penned by Nida Fazli:

(Pictures courtesy mishrasurya.blogspot.com, www.greaterkashmir.com)