A South Mumbai-based programme teaches the value of companionship to special needs children and opens a new world for them.

by Ritika Bhandari Parekh

Mumbai is a bewildering city for a newcomer. But give yourself enough time to observe how it works, and you will notice that it has a heart. Entrepreneurs abound and initiatives flourish here because Mumbaikars care. One such initiative is Buddeez.

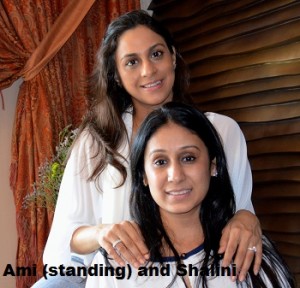

The ‘Buddeez’ programme was started four years ago in South Mumbai to offer friendship with a difference. Started by South Mumbai residents Ami Mehta Kothari and Shalini N Kedia, the programme pairs special needs children with normal ones, thus giving each a chance to enjoy the joyous moments of friendship.

The ‘Buddeez’ programme was started four years ago in South Mumbai to offer friendship with a difference. Started by South Mumbai residents Ami Mehta Kothari and Shalini N Kedia, the programme pairs special needs children with normal ones, thus giving each a chance to enjoy the joyous moments of friendship.

What the programme is about

Children with special needs may include those with learning disabilities resulting in dyslexia, or those facing delayed developmental problems causing autism. For young children like them, it is a challenge to have a social outlet for playing or even to make friends. Ami, a trained multi-sensory educator says, “Working with special needs children over the years made me realise that they do not have any interaction with other people, except for their siblings or parents. . I cannot imagine life without having friends, so I felt we needed to do something about it.”

The programme consists of students who volunteer to spend a 45-minute to one-hour session doing activities with a special child. For this, they’ve tied up with BD Somani School, which gives their 11th and 12th grade students an opportunity to become friends with special children. The students also earn grades as a part of their CAS (Creativity, Action, Service) curriculum.

Ami says, “A certain sensitivity and maturity is needed to make the special child feel happy and important. 11th and 12th graders tend to be a little mature and so we have zeroed in on them.”

Shalini says, “We hold two sessions. The first orients the mainstream children with our programme and the special children. The second session is where we talk about the child that they have to be buddies with. So four or five mainstream children who volunteer will have one special child. They are told about the special child’s likes, dislikes, allergies, favourites, peculiar traits. We familiarise the volunteers with this information, so that it becomes easier for them to get his attention.”

The volunteers are friends with the special child for two academic years. From meeting at parks to playing kho-kho or saakli, Ami and Shalini try to incorporate different activities for different children. “Some like to meet at home or play board games, while others love to roam in malls or coffee shops. We encourage volunteers to do activities that these children love,” says Ami.

There is an adult accompanying the volunteers to monitor each session. So if the ‘buddeez’ make pasta for the child that doesn’t like loud noise, the adult keeps a check on both. Having four or five mainstream children is an advantage because some special kid may just want either boys or only girls to come. So this gives the supervisors the flexibility to adjust.

Success stories

Buddeez is slowly changing how people, especially their immediate family, looks at special children. Ami says, “There was an older special child and his normal younger sibling. The younger one  would not play with the brother in the building compound. So one day, all these older boys from BD Somani came and gave him so much importance. They played ball with him and followed his instructions, which gave him a big boost. On the third day, the mother called and said the younger one took the older one down to play – all because the big guys had come and played with the elder child.”

would not play with the brother in the building compound. So one day, all these older boys from BD Somani came and gave him so much importance. They played ball with him and followed his instructions, which gave him a big boost. On the third day, the mother called and said the younger one took the older one down to play – all because the big guys had come and played with the elder child.”

Another incident had a non-responsive child, who for weeks would not play with his ‘buddeez’ group but simply ride his bike. The girls coming for the session were very disappointed with this. But after a few months when the girls were leaving, the child bid them goodbye saying, “See you next week.”

“Since the child was autistic, it was difficult for him to express what he felt. He loved the importance the girl ‘buddeez’ gave him,” reveals Ami.

Shalini adds, “In fact, we make a point to tell them at the orientation that some children will not respond, but don’t give up. They want you there, if they don’t want you, they will push you out.”

The project has the potential to sensitise school children and instill a sense of fulfillment and achievement in them. “They learn to think on their own,” explains Ami. “I remember when we took this child suffering from a lot of allergies and needed gluten-free and dairy-free food, to Priyadarshini Park at Nepeansea Road. He saw an ice-cream stall and demanded one. But the buddeez volunteers realised that he could not have the ice-cream because of his allergy. So one bright child comes up and says, ‘Oh! But he can have orange ice-cream.’ And so we went and got him an orange candy. It makes these children look out for solutions wherever possible.”

Volunteer to be a buddy

“We definitely need more volunteers,” says Shalini. ‘Buddeez’ is currently based only in South Mumbai. “We have special children from Bandra and Chembur who have approached us, but the lack of volunteers makes it difficult for us to go there,” Ami says.

Shalini says, “The attitude that friendship is a luxury for children with special needs, requires a change. It is a necessity, so instead of only working on their reading, writing, math and cross motor skills, we should make an effort to teach them friendship.”

If you wish to volunteer your child for ‘Buddeez’, you can contact Ami Mehta Kothari at +91 9820199092 or Shalini N Kedia at +91 9820028730.